=By= Gaither Stewart

“Any nation’s victory against imperialism is our victory, as any defeat is also our defeat.”

CHE GUEVARA – A HERO OF OUR TIMES?

Superhuman requirements. Perhaps the real hero is still a figure of myth as in the ancient Greeks when the heroic was divine and there was no clear distinction between super humans and the gods.

More reductively we should speak of the heroic actions of which people are capable at certain moments, under particular emergency conditions. Heroic acts may be spontaneous and instinctive, or acts of desperation triggered by fear, or a one-time display of human decency or duty to dive into a raging river to save the life of a child. However, as often the case, the heroic action may be an ego-driven and temporary urge to perform an act of bravado, a pose for show. Sorry for that! In a way I hate that affirmation.

But then some solace! For there are those precious few persons so obsessed by a positive idea that they dedicate their entire (often) short lives to one idea in the most heroic of fashions. Lenin is an example: his life was the Russian Revolution … and he changed the world. Ernesto Guevara’s obsession was world revolution against imperialism. Neither family—parents, wives and children—nor even the Cuban Revolution and Fidel Castro succeeded in deviating el Che, the man from Argentina, from that one objective: revolution against imperialism.

So the real HERO does not exist only in myth.

While living in Buenos Aires in 2007 I acquired a book by the Argentinean journalist, Julia Constenla, Che Guevara, la vida en juego (Che Guevara, Life At Stake). Moved by her first acquaintance with Ernesto Guevara that lasted several days at a conference of the Interamerican Economic and Social Council in Punta del Este, Uruguay in August of 1961 and a lifelong friendship with Ernesto’s mother, Celia, the Argentine writer offers new materials about the Latin American revolutionary’s extraordinary life. Her three hundred-page biography is illustrated with hundreds of photos, letters, papers and drawings, many of which had never before been published, of the man who became el Che. The documentation for the book plus videos were then shown in an exhibit in the Centro Cultural of the Buenos Aires barrio of Recoleta in 2007 near my residence.

There is Ernesto in the video and photographs, the newborn child in his mother’s arms in Rosario in 1928, his features already recognizable. There he is on his bike traveling through South America; there he is with wives and children, with his companions, then, there is a victorious Che in Cuba, a defeated Che in the Congo, riding on donkeys with his rifle in his arms, and there he is reading, writing, revolutionizing. And there he is, at the end, a prisoner, weak, dirty and wounded, in La Higuera, Bolivia. He is about to be executed. And then, there he is, Ernesto Guevara, el Che, dead.

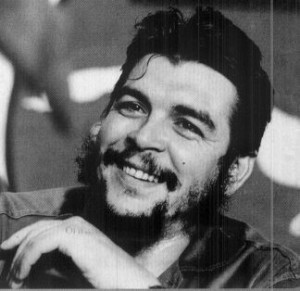

Posters hanging on the walls of youth of the world testify that Ernesto Che Guevara is widely considered a hero of our times. A profound explanation of the universal appeal and impact of this single Argentinean is found in the words of Jean Paul Sartre that “Che Guevara was the most complete human being of our age.”

I have long wondered what took place in some brain cell of that young Argentinean, Ernesto, to transform him into the man of action who became the idol of generations of world youth. For if he had not become a revolutionary, he would most certainly become a great writer.

Let’s see: he arrived from the provinces to the metropolis of Buenos Aires, a handsome, smart young guy, both John Keats and Karl Marx in his head, who wanted to make good, to make a mark, to leave a footprint. He wanted to divest himself of everything provincial and to distinguish himself in the world at large. But such considerations are reductive, in fact not even applicable for a man who wanted the whole world.

From Buenos Aires he wandered off with a friend on their bikes and ended up in Guatemala at the time the small country was experimenting with Socialism under Jacobo Arbenz. And his life began to change.

Here I turn to Wikipedia for details: Elected President in 1950, Arbenz’s modest policies of land reform and other social measures like eliminating brutal labor practices, displeased the United Fruit Company and the U.S. government who considered it Communism. In 1952 President Truman approved a CIA plan to bring down the Arbenz government. The operation was aborted because it became too public.

Then President Eisenhower, elected that year on a platform of a harder line against Communism, authorized another CIA coup d’état (John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles in the lead) with an invasion, bombings of Guatemala City and psychological warfare. Arbenz resigned and the United Fruit Company and the CIA won. That coup reinforced Guevara’s anti-imperialistic instincts.

Those events had a galvanizing effect on the 22-year old Ernesto Guevara, prompting him to move up to Mexico City to the north where he joined up with Fidel Castro, only two years older than him.

Now Ernesto was helping to make a real revolution. He was one of its leaders. He walked the streets of Mexico City, a still rather provincial city, nothing like the Buenos Aires he had left, but it was another world capital to add to his “captured places”. A place to spend his personal ambition (he was still emerging from the distant provinces of Argentina) and at the same time to fight the Yankee imperialists.

The Cuban revolutionaries, Fidel and Raul Castro and Camilo Cienfuegos, took to calling him Che, the Argentinean comrade. He began smoking his symbolic cigar and adopted his famous beret with the red star. Perhaps he was still speaking in his Argentinean accent while learning the rapid fire Cuban of the revolutionaries; they were all heroic young men about to change the political landscape of all of Latin America.

In an article in the leftwing Buenos Aires daily, Pagina 12, Julia Constenla described her personal meetings with Ernesto Guevara across the Rio de la Plata in plush Punta Del Este in Uruguay where she was covering that conference organized by U.S. President Kennedy “to discipline the Latin American continent.” Though Cuba was not to have been invited, after complex diplomatic maneuvers, Che (by then a Cuban citizen) arrived to represent Cuba. Also Guevara’s parents came and they lived in the house of the journalist Constenla. There began her days together with Ernesto Guevara and his parents.

In an article in the leftwing Buenos Aires daily, Pagina 12, Julia Constenla described her personal meetings with Ernesto Guevara across the Rio de la Plata in plush Punta Del Este in Uruguay where she was covering that conference organized by U.S. President Kennedy “to discipline the Latin American continent.” Though Cuba was not to have been invited, after complex diplomatic maneuvers, Che (by then a Cuban citizen) arrived to represent Cuba. Also Guevara’s parents came and they lived in the house of the journalist Constenla. There began her days together with Ernesto Guevara and his parents.

“I was not aware that I was involved in world history but only with one of the Barbudos of the Cuban Revolution. They had been in power two years in Cuba, Fidel and Raul Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos and Che Guevara. For days I had meals with Ernesto, interviewed him, conversed with him. He was very self-sure, with an extraordinary capacity to go straight to the point, had an acid irony, and was very seductive: when he entered the conference room everything centered on him.”

The journalist-writer says that by the mid-seventies, after Che’s death and the establishment of the dictatorship in Argentina, she realized he was one of the most important persons of the XX century. “He went down in history as the best our century could produce. In Mexico and in the mountains of Cuba, Ernesto became the famous Che.

“Before, he was a young Argentinean, brave, generous, intelligent and politicized, but not yet el Che. I see in him a level of commitment greater than I’ve ever known.” The video shown at the exhibit of him in Cuba shows a man constantly among the masses, talking, explaining, working. Electrifying speeches that many of us leftists dream of pronouncing ourselves. A man of the new state of Cuba who traveled to China and met with Mao Tse-Tung, met Nehru in India, Khruschev in the USSR.

“After his defeat in the Congo he could have returned to Cuba for a comfortable life of work and study; instead he chose to go to Bolivia. His level of commitment is incomparable. Therefore people who believe they are followers of Guevara because they have a poster of him sicken me.”

The Constenla biography denies the rumored rupture between Fidel and Che as the reason he went to Bolivia, labeling such charges as propaganda to denigrate the Cuban Revolution. She says that Che Guevara always recognized Fidel Castro as the chief. Castro on the other hand gave him the most important assignments. Though Castro did not agree with Che’s adventures in the Congo and Bolivia, he accepted his ideas.

Constenla also rejects the idea of Guevara’s suicide at the end: “He was in Bolivia to win or to die!” He lost. She recalled the strange coincidence that some eighteen people—Bolivians and others—involved in Che’s almost certain assassination died soon after in still unexplained circumstances.

Since Italy and Argentina are considered cousins because of the huge Italian immigration there, the Italian Left has strong feelings for the figure of Che Guevara. The Italian journalist Gianni Minà did a major interview with Castro back in 1987, which regularly resurfaces when news concerns Castro, especially since the Leader’s retirement.

In that long interview of many hours spread over several days Minà concentrated on the figure of Che Guevara and his revolutionary vocation. Castro stressed el Che’s altruism, his determination, his impulsiveness and his fear that the revolution in Latin America against imperialism would end like the others.

About Guevara the man, Castro recalled that when they were in Mexico together, Ernesto, despite his asthma, was determined to scale the gigantic Popocateptl peak near Mexico City. He never succeeded but he never gave up.

Che Guevara believed above all in the exportation of the revolution. And for him Bolivia was a stepping-stone back to his native Argentina. First Bolivia, then Argentina. As usual his foresight was striking. The explosive year of 1968 was just around the corner and Che Guevara was to be its symbol.

Now again today Leftists consider Bolivia a key to the future of a democratic Latin America. Readers might be aware that the socio-political movement of miners and peasants headed by Bolivian President Evo Morales emerged from the resistance that el Che had furthered forty years earlier.

Some political observers credit Che Guevara for transforming the Cuban nationalist Castro into the Latin American revolutionary he became. (Romantic thought!) Maybe it is true. For on every occasion Che’s slogan was ‘resistance to imperialism’. He must have hammered that idea into Castro’s head.

At the time of the great escalation in Vietnam in 1964-66, Guevara created the phrase of universal resistance: “Create two, three, many Vietnams,” a slogan that reverberated in Germany in the minds of the “terrorists” of the Red Army Faktion, and from there to the Red Brigades in Italy.

In his “Message to the Tricontinental,” the then newly formed Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, a paper written before leaving Cuba for Bolivia, then published in April 1967 in the organization’s magazine Tricontinental, under the title “Create two, three…many Vietnams, that is the watchword,” Che wrote:

“How close and bright would the future appear if two, three, many Vietnams flowered on the face of the globe, with their quota of death and their immense tragedies, with their daily heroism, with their repeated blows against imperialism, forcing it to disperse its forces under the lash of the growing hatred of the peoples of the world!”

Che’s credo was, “Any nation’s victory against imperialism is our victory, as any defeat is also our defeat.”

Among Ernesto Guevara’s many epiphanies on the road to world revolution was that of “guerrilla warfare”. Resistance, resistance and again resistance. Guerrilla warfare was the shortcut to the victory of Socialism and the birth of the New Man. He must have first seen the light after the CIA crushed the Arbenz revolutionary government in Guatemala. Like Saul on the road to Tarsus, his eyes were opened and he became a revolutionary.

Maybe he left Cuba and a life of ease for Bolivia because his vision was broader in scope than that of Castro. In fact, he had never belonged exclusively to Cuba. From Guatemala to Mexico City, from Cuba to the Congo, East Europe, Asia, his vision became universal. In Algiers, nine years after the CIA coup in Guatemala, in his last recorded major speech he criticized the Soviet Union and socialists countries for doing too little to help developing countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa and for not supplying arms to the poor to rise up against their oppressors.

Shortly afterwards he left Cuba for Bolivia, where he died. Twelve, 12, only twelve fast years had passed since he experienced the CIA coup in Guatemala. That may have been the catalyst for his dedication to world revolution: he was a young leftwing university graduate looking for adventure before; he was a revolutionist afterwards.

Protest and resistance are major phenomena of the modern age, part of contemporary vocabulary. Though often linked together, they are not the same thing. In rich Europe and United States we are familiar with protest against injustice. Protest can be easy and immediately rewarding. But you can protest, then go back home to comfort and ease.

Resistance, as indicated by the dean of Argentine writers, Ernesto Sabato, against all-pervasive power, against the system that stands behind injustice, requires commitment. Resistance and commitment like Che Guevara’s are difficult, a hard way of life. His kind of resistance demands your life; its price is high.

Che Guevara was not a saint. He condemned to death traitors of the Cuban Revolution, according to his belief that in a revolution “you either win or you die.” And he allegedly once said that if the Soviet missiles installed in Cuba were under Cuban command they would have been directed to American cities.

True or not, that shows the stuff Ernesto Guevara was made of. And it underlines his belief in resistance and the revolution. Che Guevara did not become a model for the IRA in Ireland and other European leftwing terrorists as well as for Islamic fundamentalists because of saintliness. Revolution was not a tea party for el Che.

His real legacy was his own life. Most photographs of him show the man of action. Handsome like the photo above, intelligent, writer, doctor, political leader and revolutionary, traveling on his Homerian odyssey through all of Latin America and the Third World.

Movements of resistance, rebellion, revolt and revolution have always been rich in slogans and rituals and symbols that are more powerful and unifying than speeches: the red flag and the hammer and sickle mean resistance. A revolutionary movement needs symbols reflecting its ideology. The Cuban Revolution itself is such a symbol for resistance against imperialism everywhere. Che Guevara himself is a symbol. Since no movement is political without an ideology, we do not mistreat our symbols. They encourage the vanguard and work wonders on the people. The Internationale anthem stirs our emotions. Every society makes some objects sacred—totems, animal images, gods, holy books, flags, or even concepts such as freedom or democracy. Rituals bond members of the society. Symbols inspire devotion and loyalty among those who identify with them.

Ernesto’s beret with the red star and his eternal cigar gave vigor to the Cuban Revolution and linked it to world revolution.

As a result of my Buenos Aires experience and my love for Argentina’s great writers like Ernesto Sabato and Jorge Borges, I try to imagine what the conservative Borges might have said about his fellow countryman, Ernesto Guevara. He would have been curious and intrigued as he was about the Buenos Aires underworld but I wonder if the effete intellectual Borges would have been able to consider Che Guevara a hero of our times. …

Yet, yet, yet, just as I have wondered about Ernesto, who knows what ticked in that huge bourgeois brain of Borges. Both of them, at the end, had their sights set on Argentina and their ways might just have come together, arriving from totally different directions. I like to hope so.