WWhere do human rights come from? Who decides which laws are just? Do other humans like myself decide what our rights are and which laws are just laws? Or is there a source superior—nature and morality—to which oppressed humanity can turn for justice

The controversy over who determines the rights of man and the laws that govern us has confounded thinkers of all times. The dramatist Friedrich Schiller noted that when people cannot find justice in any other way, they can reach up to the sky and pull down their (divine?) rights.

The travail of Sophocles’ Antigone begins when she learns she was born of the incestuous union of Oedipus, the former king of Thebes, and his own mother, Jocasta. After the blindness of her father/brother, Antigone follows him into exile, before returning to Thebes after his death to try to reconcile her brothers quarreling over the throne. Instead the two warring brothers are both killed and Creon, Antigone’s uncle, becomes king. Creon honors the brother who defends Thebes but forbids the removal of the corpse of the second, condemning it to rot as a traitor.

Out of love for her brother and convinced of the injustice of the command, which she believes violates divine law, Antigone buries his body secretly. For her crime, Creon orders she be buried alive in a cave.

This complex story is the polarization of one of the basic elements of the relationship between man and society—the challenge to public Power by the private individual … and Power’s reaction to the challenge. Since then, Antigone’s act of burying her brother has been repeated down through the centuries as women have risked all to bury their dead men/warriors.

King Creon: “Shall the mob dictate my policy…. Am I to rule for others, or myself?”

Haemon (King Creon’s son), pleading for the life of his fiancée and Creon’s niece, Antigone, who has violated the king’s law: “A State for one man is no State at all.”

Creon, who has usurped power illegally: “The State is his who rules it, so ‘tis held.”

Haemon: “As monarch of a desert thou wouldst shine.” Then later, sending his father to the devil, Haemon adds: “Go, consort with friends who like a madman for their mate.”

When Creon, despite his son’s threats to join Antigone in death if the king-dictator maintains his edict, the Chorus charges both king and submissive people:

“Mad are thy subjects all, and even the wisest heart

Straight to folly will fall, at a touch of thy poisoned

Dart.”

“Yet,” the Chorus adds to Antigone: “it is ill to disobey

The powers who hold by might the sway.

Thou hast withstood authority,

A self-willed rebel, thou must die.”

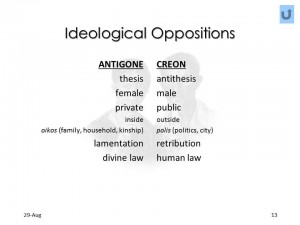

The confrontation between Antigone and Creon reflects the dialectics of Western society in all its political, social, moral and legal ramifications. The reading I have given here to the tragedy is socio-political—the individual vs. Power.

The heart of the tragedy lies in Antigone’s admission that she committed the act—she disobeyed the King’s edict and buried her brother’s body. Since her father/brother Oedipus was unaware of his crime of the murder of his father and of incest with his mother, his crime was excusable. Antigone’s crime on the other hand was a conscious act of disobedience to the law as laid down by the usurper, Creon, and therefore legally inexcusable. Let us say, comparable to the refusal of people of southeastern Ukraine to obey the oppressive laws of the illegal government of Ukraine in Kiev.

Since Antigone admitted her action—but not her guilt as Creon insisted she do—her defiance of Power appears not only as a demand for justice, an expression of the greatest love, a passion for an ideal and conformity to an ethical norm superior to the public one. Her claim for individual rights collides with requisites of the State. Hers is more than an act of feminine courage, even more than a death urge, the limit that humans can hardly cross. Hers is an act of heroism for true justice.

Her act is a symbol of the emergence of the superior individual law vis-a-vis Power. This tragedy of 2500 years ago turns on the politics of the private spirit and the violence which political-social change exacts on the individual. This is the dividing line of the abyss separating individual man and society.

A terrible beauty on the one hand, a terrible ugliness on the other. The clash of private conscience and public welfare. Yet in modern times both private conscience and the concept of public welfare have weakened.

First demanding justice, and then adding that her dead rebel brother stood “outside” the law, Antigone stands on the lip of that abyss before she disappears from the action of the tragedy into a death so un-understood that the Chorus called her “inhuman.”

Though Antigone admits she broke the written law. ethical man forgives her in the name of an unwritten law that exists above and beyond the public law, which idealists in all times would make part of written law. She is legally criminal. But only to the extent that her act enters into an ambiguous territory of the very concept of law.

So the point is clear: we are speaking of the law of the State as opposed to ethical law, the immutable unwritten laws of the skies that Schiller meant, laws that may never be written. For example, not even the holy scriptures condemn war unconditionally, which every thinking man knows is criminal. Antigone is symbolic of that unwritten law, eternal, universal, perhaps divine. She exists somewhere in a shadowy realm that contemporary men strain to understand.

Though that unwritten ethical law appears as the most elevated part of man, her defiance in defense of that law borders on what modern theorists would most likely define as terrorism … because of her fanatical “longing for death” in defense of that law. Yet her choice is not distant from the concept of the divine rights of man that lie in that same shadowy territory. In that sense her choice is transcendental for mankind, because it is linked to the good.

Instead, Creon at first justifies his severity in application of the law—though public, it is his own arbitrary law—in the name of the good of all, as per Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor. His will becomes law. And he would compel the ethical individual to obey his arbitrary law as does Kiev in the Donbass. In Creon’s application of the law, he exceeds ethical law, basing his authority on his own desire.

The unfolding, the denouement and conclusion of Sophocles’ Antigone not only do not lead to resolution but to irresolution. Instead, the action intensifies Antigone’s defiance, causing a cycle of death in which things go insane with the suicides of her fiancé Haemon and his mother and Creon’s wife.

In that sense the entire cast—Antigone, Haemon, and Creon himself—stand on the edge, at the limit of life, somewhere between life and death. Ambiguity reigns supreme. Antigone evokes laws of heaven and earth, yet she exists within the presumption of criminal guilt—which in a narrow view is only grieving for her dead brother—and in a sense not even clearly in opposition to Creon’s edict in the name of the good for all. Strangely, they both claim the gods are on their sides. Some philosophers have concluded that Sophocles’ Antigone is a God’s child, a Christ figure, emerging from the tomb to live through the millennia until our day.

And Creon himself, was he only evil? That too is an eternal question: Was his edict a kind of social heroism? Or was his act purely arbitrary, a case of, “I want to do this thing.”

In the end—and as a boon to the conscience of those persons dedicated to the role of the just social state—Creon, the man of State, does come to regrets. Though here I am tempted to argue with myself, I recognize that Creon understands and appreciates Antigone’s stance and that he is aware that she too appreciates his position.

Here we stand before the familiar duality of life: between what we think we desire to do and what we actually do. Between enlightenment and madness. Illusion and delusion.

Meanwhile, in Sophocles, the Chorus, that is, the public and society, discerning or not, vacillates in its support, first for the man of State and Power, then for the higher right. For the Chorus, Antigone is less than human. She no longer counts, she is out of the world, a substratum, to be compared to the unconsidered masses, the non-represented, non-participating, non-voting majority of America who take no role in the exercise of Power.

At the end of Sophocles’ tragedy, one wonders what kind of gods they are all appealing to since they all believe they are acting within the mandate of the gods. In my reading, Creon is the representative of arbitrary Power which the oppressed, for whatever their reasons, have the divine right to doubt, question and bring down to make place for a just society.

Freedom requires that man act polemically, precisely in order to realize both himself and a just society. In order to reject the fatalism that leads us to accept that what will come to pass will come to pass. People die but others must go on. Life will go on.

One must participate in order to be part of continuing life. But when the laws of the land are in conflict with justice, when Mother State is no longer just, then acts which Power decrees are criminal, acts which in fact must become violent and revolutionary, are not only just, but necessary.

In my reading, Antigone is representative of the conflictual revolutionary ideal. One recalls the proverb, “if you strike at the king, you must kill the king.”

First written in Providence, Rhode Island, February 2007

First re-worked in Buenos Aires, September 2007

Finally re-worked today in Rome, January 13. 2016

C4