=By= Gaither Stewart

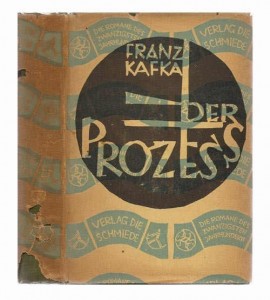

So as not to lose any potential readers of these columns before I have even gotten started, I offer d’emblée an apology for these ‘thoughts about fiction writing’, which I promise not to repeat. At least not frequently. But it seems important to spell out at the beginning and admit that my preference for writing fiction over non-fiction has ever less significance in modern times (explained in more detail below), and nonetheless to show some of the reasons for that preference in the first place and how I see the current situation of the literary composition in change.I think of the modern citizen who knows that he is at the mercy of a vast machinery of officialdom whose functioning is directed by authorities that remain nebulous to the executive organs, let alone to the people they deal with. Walter Benjamin (1892- 1940 in Illuminations, in reference to Franz Kafka’s novel Der Prozess, (The Trial) written, 1914-1915.

Secondly, I also hope to lay the first brick in my structured attempt to illustrate to the publisher of The Greanville Post and of this site itself the proximity of fiction and non-fiction today. showing the rapidly narrowing differences between the two. So please, readers and publisher, bear with me.

Here goes.

As a fiction writer, I love the short story—long traditional ones too—and believe I will always return to the kind of storytelling the short story accommodates. However, in recent years my major attention has been directed to the novel. The novel, so much debated, so widely discussed, so maligned and so fragile and so sensitive to changing times and changing readers living enormously changed lives from those experienced by preceding generations, to the extent that reality, the reality that writers constantly seek, has itself changed. For these reasons, the survival of the novel as an art form is a pertinent question of our times. Pertinent also because it is a reservoir of values and morality, and thus it plays a major role in the planetary struggle between good and evil.

However, I too am uncertain about the use—or even the adaptation—of old forms of the novel to describe our rapidly changing times. Lived life today is so rapid. Communication is instant. There is little time for the distracting detailed storytelling as once took place during dusty slow rides in carriages to cover fifty miles for a cup of tea with a distant friend. Traditional fiction has come to seem a vestige of the past, at times a luxury, that no few readers reject. On the other hand, even though a great deal of up-to-date fact and reality (Ah, the eternal search for reality!) enter into any story, the fictional aspect of the novel nonetheless remains—the imaginary and the what-ifs? of life.

Since political events determine to a great extent the tenor of our lives, in much of my work the novel has already become “the political novel” or, as someone has called it, “factual fiction”. The bare story itself is set in real places where real history is being made from minute to minute and real political events are taking place, which for some readers of pure traditional fiction is off-putting because political reality in these turbulent times can easily overshadow the story itself—romance or adventure or pure action—so that non-fiction seems to them more apropos.

Nonetheless, I find that the invented characters, the geographic locales, the love affairs, the violence, the hate and pardon, provide the framework for the personal passions and fears, the successes and failures, so necessary to flavor the story itself and provide characters and words and concrete ideas arising from daily realities with which the reader may identify more easily and thus be lured into the political and the ideological aspects of the novel.

E. M. Foster in Aspects of the Novel affirms, reasonably, that time must always be reckoned with: “… a story is a narrative of events arranged in time sequence.” Events succeed one after another like the days follow one after the other. The writer is (more or less) compelled to follow some time sequence even if very lightly, although some writers today find that concept old-fashioned as shown in novels of this millennium in which time is largely ignored and sometimes truant no matter the risks to probability and possibility. In my search for reality I accept the solid storytelling truth of the role of time. Not that time is necessarily constant or honest but the clock continues to play its role.

What happens within the time span of the story is the essence. Within time, emerge passions, intrigues, crimes, war … and, as a result of changing times, the writer’s judgments and considerations of real values and of their great container, Morality. Within this churning and straining within time, intensity grows and grows as layer after layer of the story itself, each layer perhaps separate and mysterious and inexplicable at the time it occurs, merge and come together into something or other cohesive.

I mean to say that the most esteemed fiction writers whose work has only the thinnest guise of fiction are instead, let us say, philosophers who use the barest story line as an allegory to express the most abstract feelings and subjective views of the innermost of the human being. For example, Kafka is not so highly considered, nor is his work so complex, simply because he wrote a story about a man who is transformed into a cockroach or a man being tried on unknown charges.

I am presently reading an essay on Kafka by Walter Benjamin in his book, Illuminations. I first read Kafka when I was not only too inexperienced to see the resemblance of Kafka’s work to poetry, but was furthermore blind to his allegory. I did not recognize that he was writing about how life and work are organized in our society—which he relates to destiny. Sad situation for man! In a conversation about (pre-WWI) Europe and the decline of the human race Kafka once said to his friend Max Brod that “we are nihilistic thoughts, suicidal thoughts that come into God’s head. Our world is only a bad mood of God” … and concluded that “there is no hope for us.”

In that sense, Kafka found that ‘man is always in the wrong with God.’ And in his renowned novel, The Trial, man is on trial by higher authorities (God, Power, Big Brother) but never clearly understands on what charges. Therefore, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) could write during the Nazi madness in Europe in the 1930s-40s: I think of the modern citizen who knows that he is at the mercy of a vast machinery of officialdom whose functioning is directed by authorities that remain nebulous to the executive organs, let alone to the people they deal with. The only hope of the accused is postponement and more postponement so that the trial proceedings do not turn into judgment. Therefore, Benjamin concludes, Kafka’s shame. Shame both for himself, the defendant, but shame also for the others, the judges. Illuminating idea!

Another contemporary conclusion was Franz Kafka’s views on progress: “To believe in progress is not to believe that progress has already taken place. That would be no belief.” He did not consider the age in which he lived as an advance over the beginnings of time. His was a prophetic deduction indeed. Such a statement would be valid in any discussion of progress today. He predicted our current world.

It is said that Art stands still ( not completely true as Kafka shows over and over) while History moves. The literary writer’s art has always been found in the manner of the transmission to the reader of the author’s passion, without which no life, no story, no novel, no non-fiction is valid. Yes, the passion! The passion from which emerges the writer’s fantasies, his most intimate admissions, his insecurity, his fears of failure coupled with the hope of success, and with luck stumbling onto some magnificent prophecy that one day will justify and reward him.

Gaither Stewart

Rome

January 6, 2016

There remained a fine line between truth, lies, science and fiction. Khafa crossed that line and carried us into a place where we could embrace our fears with writing and creative arts. Today that line has been erased and the sand is gone. But oceans of imagination and dreams remain. He deserves our thanks.

Timothy Flanagan

Missoula

January 9th, 6:52am