=By= Gaither Stewart

THE WORLD’S FIRST ARMS MERCHANTS

The men fat and sexually ambiguous. The women rich, free and promiscuous. An ancient superstitious life-loving, sea-faring people enriched by an arms industry based on iron and on wine cultivation. By the sixth century BC, while Romans were still barbarians, the enterprising Etruscan people had developed a dynamic society in ancient central Italy which they dominated for centuries. The people partied, the men sailed the seas and fought wars, the women sold love and slaves did the work. The ultimate downfall of their opulent civilization has been attributed to their soft, fun-loving life.Yet Etruscans had special qualities and natural resources that enabled their great confederation to rule the Italic peninsula from Rome to the Alps. Ancient Rome’s first kings were Etruscans. On the other hand, the Etruscans were long misunderstood, misinterpreted and slandered with tales of their “cities of the dead”, their haunted tombs and their cult of death.

Today, despite vast acquired knowledge about them, the Etruscans remain one of the most enigmatic of ancient civilizations whose culture came to be known chiefly from their exquisitely frescoed tombs with their suggestive phallic symbols spread over much of central Italy. History, often brutal and reductive, tells one version of the story of the Etruscan civilization in a few words: They appeared, flourished for nine centuries, their kings ruled Rome for hundreds of years, and then they declined and finally vanished, absorbed by the rising military Roman state.

Still today, even their origin is a tricky question. By the same token, one might ask where all those peoples roaming around the East after the Trojan wars came from? Some specialists say the Etruscans came from Lebanon. Maybe they were Sumerians. Or they came from the Sahara when it dried up. Or just maybe they were autochthonous and had lived here all the time.

The Etruscan city of Vulci. Robin Iversen Rönnlund.

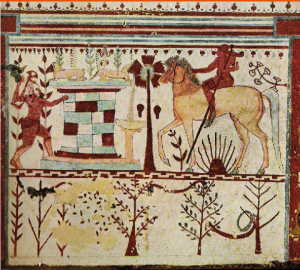

In fact, Etruscans are omnipresent on the Italic peninsula, much of which they inhabited and ruled: in modern times a stone tablet was found in a field in north Italy at the foot of the Alps with a name written on it in Etruscan: Larth Iasaziz son of Esia. The remains of an important Etruscan city, Veio, famous for having resisted Rome’s armies for three centuries, is within the Rome township where I live today, with caves and gorges, a museum and well-preserved archeological remains. Moreover, the name of the administrative Region of Tuscany derives from Etruscan lands then called “Etruria” (a name very much in circulation in modern Italian) as does the relationship Etruscan=Tuscan. Etruscan frescoes in their tombs depict magical religious lives of banquets, dancing, music and sex, mixed with a morbid preoccupation with the hereafter, in a life filled with demons and deities and sexual symbols. Their sacred books dealing with their rituals and accumulated knowledge constituted the Etruscan Discipline, a unity of theory and practice about the interpretation of signs. Their deities were Jupiter, Juno, Mars, Mercury, Venus, Saturn, Minerva, and their terrible God, Charun-Charon.

Although the Etruscan alphabet no longer presents great difficulties since it derives from the Greek, the language is nonetheless isolated among known languages. Apparently, Etruscans took the ancient Greek alphabet and adapted it to their spoken language. Its absence of voiced consonants, a morphology different from Indo-European languages, its extensive use of suffixes, a lack of knowledge of its verbs, and problems of the limited number of known Etruscan word roots, made comprehension of the few surviving longer Etruscan texts obscure. Though Greek and Latin translations of those texts have illuminated scholars, that is too little to reconstruct a literature that must have been rich, considering the level of its civilization. Greek and Latin authors documented Etruscan literary activity and reported on “Etruscan Stories,” vaguely identified authors and an advanced educational system. I have read that no literary historian doubts the Etruscan impact on Roman literature.

Popularly, ETRUSCAN is still associated with mystery: mysterious orgiastic lifestyle of party and song, mysterious rites, mysterious origins and that allegedly indecipherable language. Ancient myths wove a web of mystery and threat around them. The vengeance of their old gods hangs heavy over the many desecrators of their tombs and their arcane buried past. (A generation of tomb robbers made the desecration of their tombs a lucrative profession.) Though historically the Greek-Roman image of the Etruscans was of a cruel and corrupt people, in my lifetime informed tourists from north Europe have traveled to Italy just to visit the various Etruscan museums and the tombs of Tarquinia, or they visited priceless collections of splendid Etruscan table wares and vases in London and Paris. To many people today, the word, ETRUSCAN still rings sinister.

The Etruscan mysteries remained in the darkness until last century when archeologists and historians and linguists began reassessing that civilization. Etruscanologists (oh, yes, they exist!) have in our lifetime begun discovering the truth about one of Europe’s oldest civilizations. Last century, 1985 was declared “the year of the Etruscans”, which was marked by exhibits and conferences throughout Etruscan lands between Rome’s Tiber River and the Arno River of Florence.

Now a new generation of experts has deciphered the Etruscan alphabet and showed that the old experts had been wrong about everything. The Etruscans were not as mysterious as we had been led to believe. It was because no one had been able to make heads or tails of their language. Now we know much more. The Etruscan language, once little more than a secret code, has been unraveled. Some seven thousand words have been transcribed from inscriptions and tablets in the tombs, not enough to reconstruct an Etruscan literature that the Romans destroyed along with most of their culture, but enough to understand that Etruscans had simply borrowed the Greek alphabet and adapted it to their spoken language.

It comes as a surprise to learn that besides Judaism, the Etruscan religion was the only revealed faith of the Mediterranean world! Revealed through the mouth of a child uncovered by a peasant digging in the fields near the town of Tarquinia. The peasant dug up a clod of dirt that transformed and took on the resemblance of a boy. According to Etruscan teachings, the child Tagete revealed to Etruscan kings the secrets of the origins of the universe. God, the creator of all things, assigned the world twelve thousand years of time. In the first six thousand years He created sky and earth, seas and rivers, sun, moon, stars, birds and animals, and finally in the sixth millennium, man. He assigned six thousand years to mankind, after which the time of man will end.

The prophecies of Tagete and other semi-gods were collected in sacred books, the Etruscan Discipline. Those books revealed the means to interpret divine will and to affect history through rites and ritual. Through expiation of guilt Etruscans hoped to be spared the divine punishment that hangs over peoples, cities and individuals. History itself was sacred. Nothing happened by chance. Everything that happened was to announce a future event. Or it was the realization of a sign the gods had sent earlier. For the Etruscans, facts were not important because they happen at a certain time but because they arrive in order to have a meaning in the future.

Though the Etruscans were mystics, a little mad in their views of the hereafter, they were also a pragmatic people. Their economy was based on their metal ores. They made their fortune on iron. Iron was for the Etruscans what oil is for contemporary Arabs. Iron meant modern weapons. They developed iron weapons—shields, swords, helmets and arrows—that changed the nature of warfare. Being a sea-faring, money-minded people they then sold their powerful iron weapons to the rest of the world, and became their world’s leading arms manufacturer and international dealer in arms. Weapons in turn meant conquests and empires. One might contemplate comparisons with the USA/West although that thread would not get you very far. They were however rich capitalists, albeit lazy and fun-loving, and who had slaves to do all the work, man their ships, fight their wars like mercenaries today and finally even govern them.

In that sense, like the Celts in Ireland, the old bacchanal Etruscans have transcended time. People on the cobbled streets of their old city of Chiusi have the same thick necks, high cheekbones and sharp noses as the figures on the black and red vases and funeral urns studied by historians, archeologists, anthropologists and students of art.

In reality the mysterious Etruscans of yore had two things in mind—fun in the here and now and preparation for the hereafter. I have come to believe that in their search for wealth and influence their hired sailors-arms merchants reached the Americas before the Vikings. Perhaps the Etruscans perhaps had contact with the Olmec civilization in Mexico two millennia before Columbus. A cursory look at the sculptures and the features of the two peoples reveals a bewildering affinity.

After a long sleep the Etruscans were reborn when Florentine travelers exploring the deep gorges of wild uninhabited lands stumbled onto houses cut into rock cliffs covered with 1500 years of vegetation. And they literally fell into underground tombs. Colorful images of people of another epoch leapt out of abandonment, images of men with enormous erections and promiscuous women, sexual acrobatics, and everywhere phalluses.

Even today a certain silence lies over the former Etruscan country north of Rome as if to underline those ancient mysteries. Lands of deep forests and green hills and rugged mountains, of volcanic lakes, of hissing fumes and gurgling hot mineral waters rising from the earth, of rushing waters cutting through rock cliffs. Time on those still sparsely populated lands seems to have stopped. And modern Etruscanologists want both to preserve the memory of the Etruscans and at the same time debunk the mythological aspects of this people, the distant ancestors of many Italians.

Also the myth of a people dedicated to the death cult has been exposed by the images of their love for life. Not even their historical demise was mysterious. It is here that a thinking person might be tempted to draw historical comparisons and analogies: many empires have come and gone: e.g. the Persians, Alexander the Great’s world, the Greeks, the Romans, the Mongols Also the Etruscan civilization matured, peaked and then declined and vanished. But the Etruscans did not just fade away into history; in the end they were simply defeated militarily and politically by the ambitious blood-thirsty Romans and assimilated by that new world empire.

ETRUSCAN HERITAGE

So what remains of the Etruscans? What did they leave us as their legacy? Though the later Romans depicted an immoral Etruscan society and their women as whores, the reality is that Etruscan women were emancipated, emblematic of an advanced civilization. The old world in which women were inferior beings could not digest the Etruscan equality of the sexes. Greeks were shocked by Etruscan women at the banquet table with the men, by women bearing their own given names. Etruscan women even lived alone, earned their livelihood with love and accumulated wealth which they could bequeath to their children, who belonged to them, not to their fathers whom they did not even know. They were history’s earliest feminists.Mysterious Etruscans? The new image is of a less mysterious and more modern people. The Greek-Roman myth has been cleaned up. The Etruscans rehabilitated. Dynamic men of commerce and culture who also loved the good life. Like everywhere divided into castes of rich and poor, of believers and non-believers, they nonetheless had a very legal mentality, while their blind faith in the role of fate gave them pride in their individual achievements.

Etruscans today project a very contemporary image: progressive agriculturalists who perfected irrigation systems, canalization and land reclamation. Engineers who built roads and bridges using modern techniques. Doctors famous for their predictions of the future based on readings of the entrails of sacrificed animals. Their laws and religious rites were recorded in books. They were most famous sailors of the old Mediterranean world. Merchants who traded with France and Spain. Wine producers who exported to north Europe. Time has whitewashed the image of the Etruscan people even though they set bad examples for modern men and empires. Because of their mystic vein, Etruscan soothsayers were considered the wisest of all. But then, later, under Roman domination, Etruscan soothsayers were considered charlatans. Just goes to show you the potential or probable future of many of man’s religions and fundamentalisms.

Soothsayers, sex festivals and early Europe’s leading arms manufacturers who sold shields, swords, helmets and arrows to the world. Their economy was based on their metal ores. They made their fortune on iron. Iron was for the Etruscans what oil is for contemporary Arabs. Iron meant modern weapons. Weapons meant conquests and empires.

But then, the inevitable. The Etruscans were at their acme and dialectically decline was predictable. For times change. Nations rise and fall. Civilizations are born and die. The Etruscans’ contribution finished in the Iron Age. They had inherited a spirit from the East, developed it, reached their zenith, and then collapsed under Roman firepower. We could make an analogy with the emergence of Europe and then the USA on the back of sophisticated technologies and weaponry. It has been said that the Etruscans fell because they never understood Rome. Some think the same threat hangs over imitative Europe vis-à-vis the United States today. For example when the Etruscan city of Orvieto, one hundred kilometers north of Rome naively called in Roman troops to quell a local revolt, General Fulvius Flacco marched his troops north and leveled the entire city of Orvieto instead. It was at that point that Etruscan nobles began moving to Rome and integrating into the new society. They wanted to be like the Romans! History is of course so unkind. The good times never last forever.

Yet, yet the whitewashed version of the old Etruscans can be a let-down. The mad old Etruscans we once imagined were more appealing, with all those wild rites and parties and legal piracy. It is rather sad to see it all debunked, to experience the dissipation of the old mysteries. To see the old Etruscans and the emancipated women just like everyone else.

On the other hand, enriching themselves from the sale of murderous weapons made from their iron enabling the people to live in perpetual leisure made their civilization immoral. And sick. Then, they became selfish and avaricious. A sick society dedicated to self-amusement and imitation is not a basis for survival.